We touch with our fingers and skin. Since birds’ skins are covered with feathers, this would seem to limit their sense of touch. But birds have tiny thin almost invisible feathers that likely help a bird be exquisitely sensitive to touch.

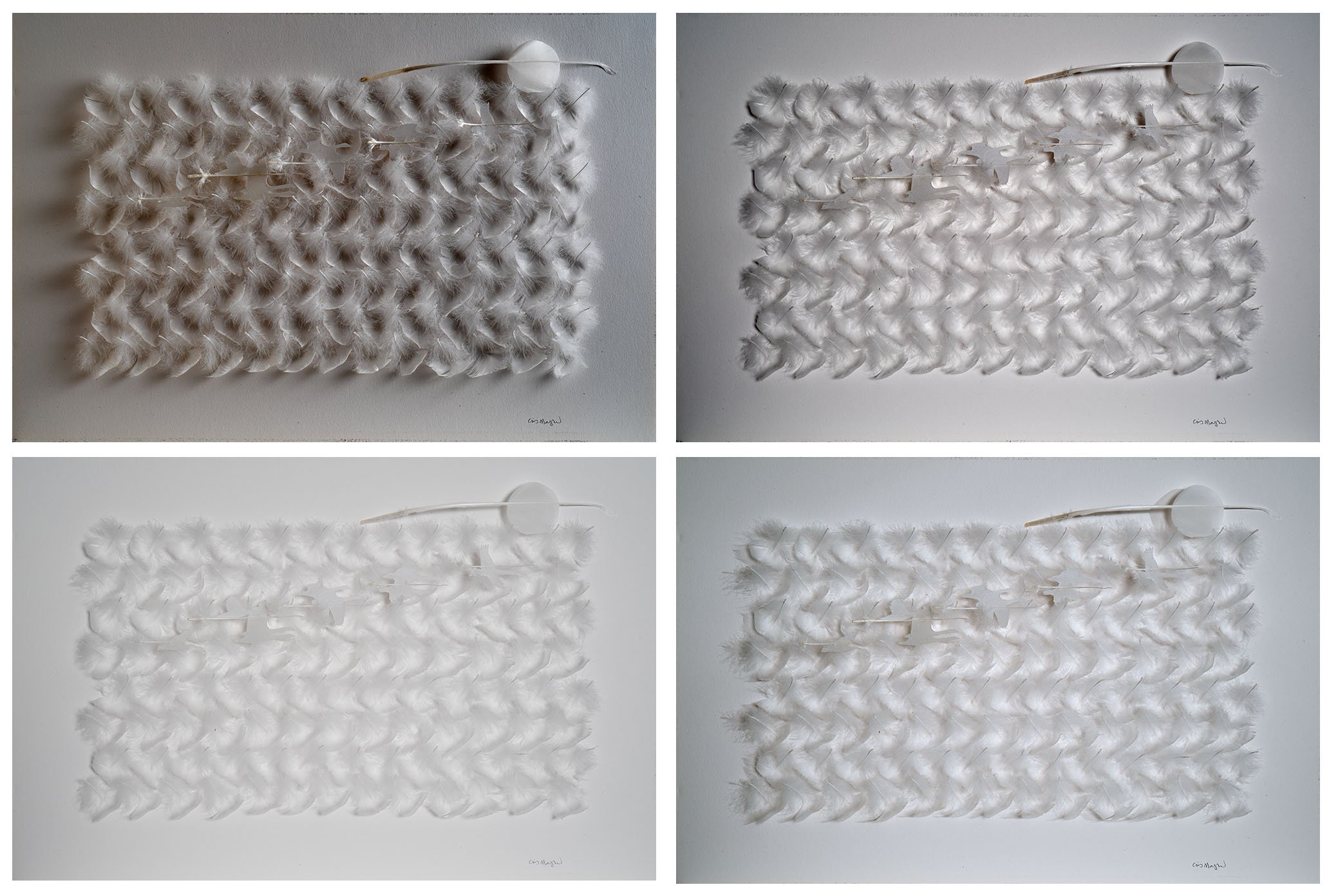

This is the best educated guess of the function of a certain type of small feather that grows next to the and underneath the big body and flight feathers that you see on the outside of a bird. They are called filoplumes. They look like very thin hairs with tufts at the end. The shafts are inserted right at the base of the body and flight feathers and into areas rich with sensory receptor nerves.

Here are a couple of ways they would work: If a body feather is out of place, the bird could feel it by the movement of tiny filoplume feathers next to it. The filoplume feathers likely act as levers enhancing the movement of the tip to the nerve-rich cells at the base where the shaft is inserted into the skin. Then the bird could know to ruffle its feathers or groom the out-of-place body feather into place.

And when flying, the filoplumes could, through the nerve receptors at their base right next to each big primary feather, tell the bird to adjust the angle of each feather according to the aerodynamic needs of flight.

*Spring 2020 issue of Living Bird Magazine