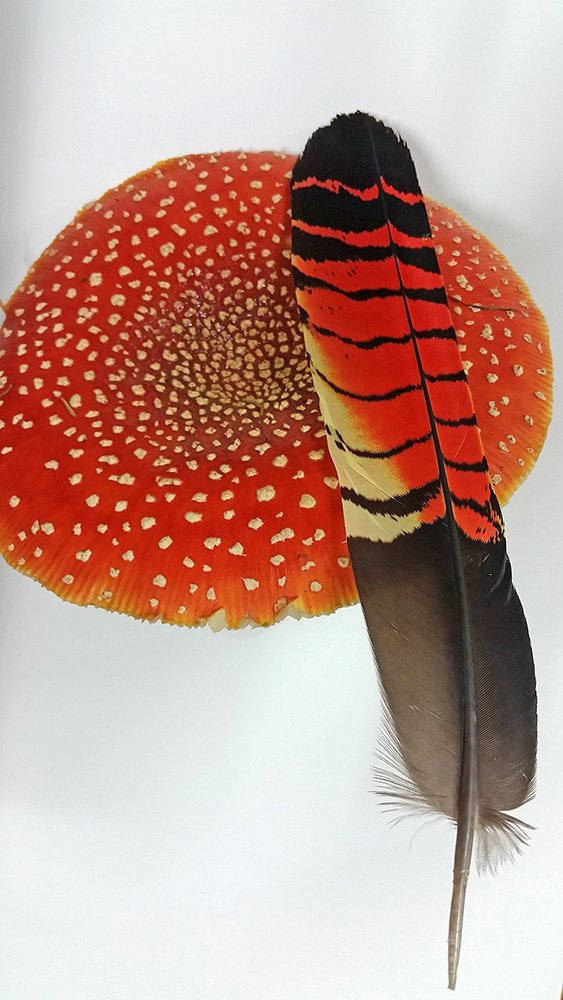

Preen detail, Capercaillie tail feather

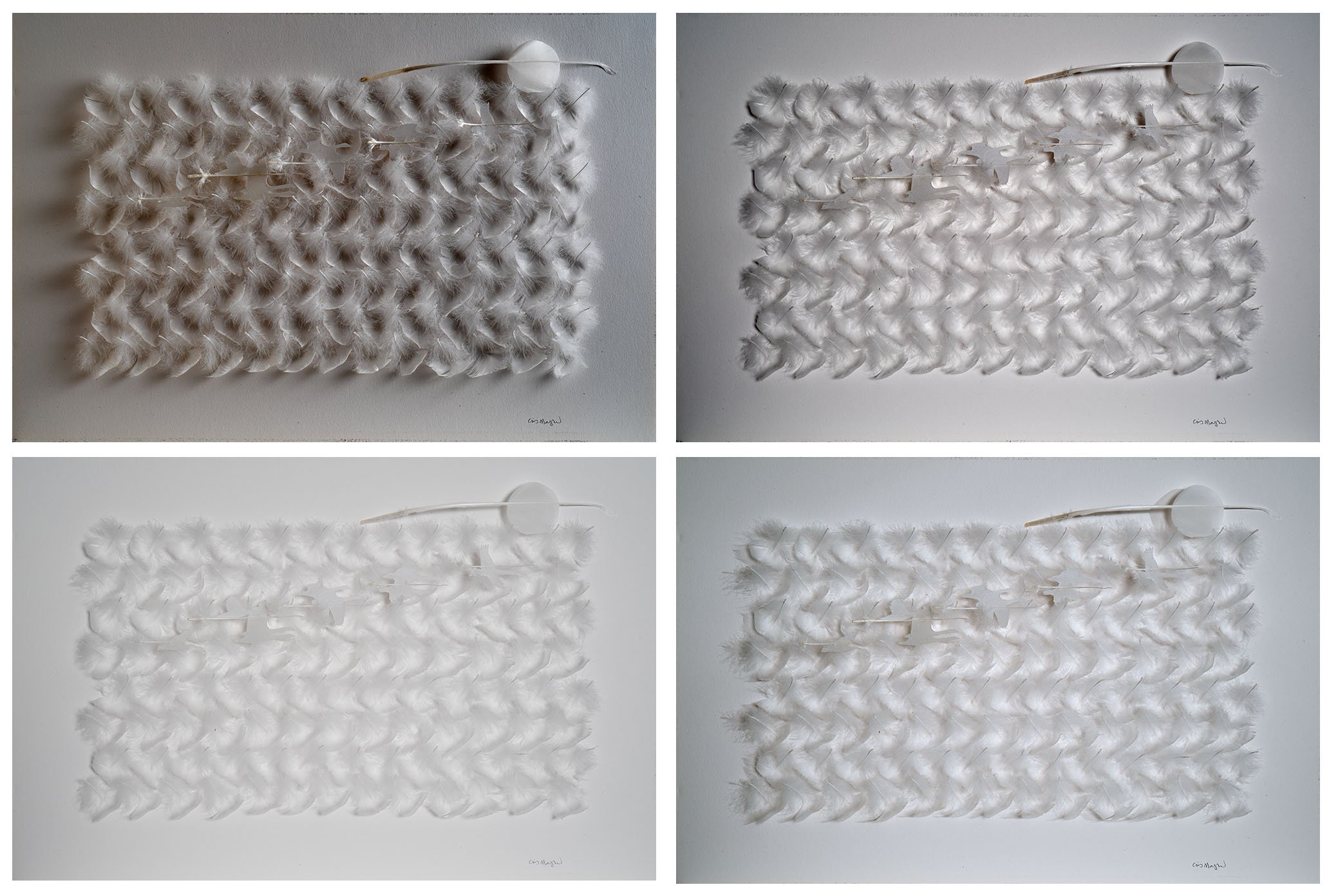

A cool thing about shed feathers is that they keep their complex structural integrity yet the bird that shed them has already grown new replacements so it doesn’t need the old feathers. They usually fall to the ground to feed small creatures that decompose them breaking the feathers into small components that can be used by plants as nutrients. Then the plants or its fruits and seeds are eaten by creatures like insect which the birds eat to grow their new feathers.

I recycle feathers into my art but it is only a matter of time (hopefully hundreds of years) before my art and the feathers in the shadow-boxes become small components of dirt to be absorbed by plant roots

Decompositional bacteria eat the feathers—even on feathers growing on live birds. They do it by using an enzyme (keratinase) that decays the keratin that feathers are made of. Fortunately for the birds, they can pretty much stop this degradation of their feathers from happening. Part of a bird’s feather care routine while preening is to rub and preen bacteria inhibiting oil that is produced by a gland near its tail on its feathers. When a bird preens in this way, it’s kind of like seeing actor George Clooney combing his treasured Dapper Dan hair gel through his hair in the movie, Oh Brother Where Art Thou.

See this write-up and more references for detail on feather decomposition by bacteria. https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Feather-Decomposing_Bacteria