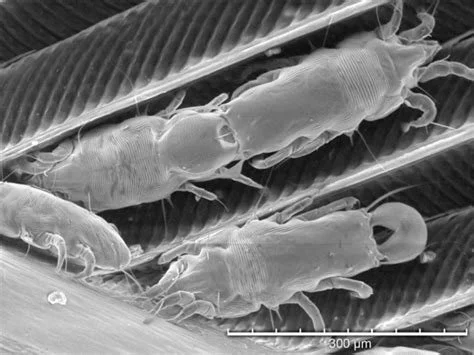

female red-tail black cockatoo feather, detail

This advice is about feather structure and applies to whatever equipment you are using, be it a cell phone or a high-end SLR camera.

Two major feather structures require you to adjust your shooting for better photos. The first is the downy part of the feather, usually at the base. The down is so fine that it disappears if the background color is anywhere close to the color of the down. Usually the down is a light color, so it won’t show up on a white background. The solution is not to take a picture on a darker background, then put it in an editing software program like Photoshop. These downy feather parts are so fine, they pick up the background color and it cannot be removed. Believe me, I have tried, used add on software, and consulted with all sorts of professional photographers—and failed. My solution has been to settle for a light neutral grey as the lightest background if I want to preserve the detail and create a lighter background

You can see a couple of examples in these photos of my work on Brenda Houston’s wallpaper. In one of the wallpaper examples, the downy part at the base of the feathers is washed out by the lighter background. Black or any darker color can make the feathers pop. But who wants black backgrounds for everything?

The second basic structure of feathers that influences how they photograph is in the fine detail of the barbs. The downy feathers are barbs but I am writing here about the barbs that make up the flat vane of the feather, above the place on the feather where the downy part is. These barbs are like branches all stuck together. They form tiny ridges running away from the shaft. Just like morning or evening sunlight creates shadows for more interesting photographs, side-lighting the feathers makes little shadows that highlight the little barb structures. Play with the angle, though I find that angling a light to shine across a feather just a little less than 90 degrees preferrable. For my photos, in addition to the side lighting, I often place another light to shine directly on the feather.

Oh, and if you want to improve your image, wash the feather first, unlike the dirty feather at the top of this blog. See my blog on cleaning feathers.